3/06/2013

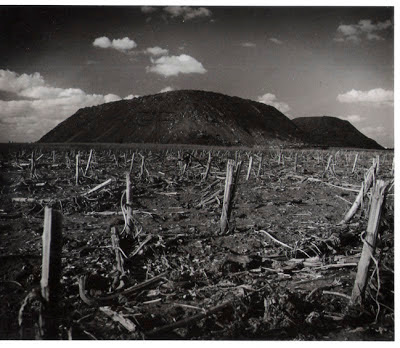

Tamir Sher / Garbage Mountain series (1998)

The mountain is a symbol of consistency, persistence, and eternity. Its origin is in the earth and its summit is in the sky and it unifies the two realms. In Jewish tradition, there are two mountains, which represent places of power, where a significant transformation in the Jewish people's psychic evolution occurred: Mount Moriah, where Abraham's faith was tested and his son was restored to him, and Mount Sinai, where the Torah was given to the Jewish people. Hiriya is an artificial, man-made mountain, and although it is the highest place in the Dan Zone (one could say, ambiguously, that it is Tel Aviv's mountain), it is nothing but a garbage dump, a mountain of garbage. In light of these givens, which are known to everyone, I have sought to heighten the tension between content and form, to expose the mountain's symbolic meanings and to juxtapose them with the mountain as a metaphor for a distinctive cultural phenomenon, which has robbed the concept of its magical power. I have attempted to make use of the transformational powers of "mountain" to turn a site of garbage into a site of holiness. I was astounded that a purposeful activity such as the removal of garbage had engendered an aesthetic form, for Hiriya is an astonishingly beautiful place, to my taste: its form changes frequently, its sides create planes which respond to changes of light and weather, its top is dentate, it is divided into two - and all these aspects make it a fascinating object to photograph. My works seek to conduct an intensified contemplation of essences and symbols, to penetrate into the psyche's eternal experience, to unravel the way along which cultured people have gone towards alienation, and to return backwards, to the basis.

Tamir Sher, 1998

3/04/2013

3/03/2013

3/02/2013

2/28/2013

A brief summary of the afternoon's welcome Manifesto

A Crippled Architect

“An architect who had never done a building, who never went through the whole process of a building, from scratch to the end of the construction, is a crippled architect. In order not to be crippled, every architect should do this at least once in his career.” Those clever words were said to me by the Israeli architect Avraham Yasky (1927-), formerly my employer and later the protagonist of my second book, while handling me the project that would become my first building. I have always been grateful to him for this.

In 1932, many years before the realization of his first project, Philip Johnson, then a young curator at the MOMA, wrote “Architecture is always a set of actual monuments, not a vague corpus of theory” (The International Style, p. 21).

Architecture has to be realized. It has to be real. You may do many things related to architecture – write, read, study, teach or even practice – but if you have not realized a project, you will be a “crippled architect” according to Yasky, or you may not even call yourself an architect according to Johnson.

Architects and Masons

While any architect can cite Adolf Loos’s famous saying “An architect is a mason who had learned Latin” (“Architecture and Education”), not only Latin, in general, has never been a part of the standard architectural education but more surprisingly masonry too has been almost completely absent from the architectural syllabi.

In fact, since the beginnings of modern architectural education in the mid 19th century, architecture schools all over the western world have chosen to provide the students mainly with representational skills - descriptive geometry during the 19th and the 20th centuries, computer assisted conception and drawing in our times. The syllabi were organized according the notion and the rhythm of the studio project, which is in general and by definition fictitious, speculative and hypothetical: it is acknowledged and understood from the very beginning that the project will remain a project, that it would never be realized or built.

Drawing and Withdrawing

Although architects like to say that they build buildings, they do not actually build. In most cases architects do not build at all; they just sit at their desks, in front of their computers, in their studios, ateliers or offices and design, draw and model buildings.

Practically, the withdrawal of modern times’ architectural practice into representation implies a progressive diminishment of the architect’s responsibility and the delegation or the outsourcing of his traditional tasks to other specialists or professionals. There would be numerous decisions that the architect will no longer have to take, and a considerable amount of information that would be irrelevant for him. More importantly, in the modern distribution of tasks it is taken for granted that there would be someone else to do the hard labor: the architect will not do the masonry.

Construction sites as micro societies

If we will try to understand architecture simply by its means of production, to think of it not only as a set of images but as a part of a social and economical process that takes place within the Real, it would be impossible not to see how the production process of a building reproduces and aggravates the social divisions between white collars (architects) and blue collars (masons, laborers), and how, regardless to our best intentions, our construction sites may appear as social theatres in which one might witness, inflict or suffer the worst of our actual class systems.

So, my dear friends, let us now get down to work and realize our thoughts and ideas with our own bodies and muscles.

Words:

adol floss,

SABA Manifestos

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)